Looks Like Rain

Iconic Music Photographer John Scarpati Shines a Light on the Dirty Little Secret of Digital Manipulation

by Michael Dukes

“I really wanted to be a painter. I really wanted to be a rock star. Ultimately, I became neither of these things—and both.” Photograph by Michael Weintraub

Is today’s technology blasting open the doors of creative expression or simply providing shortcuts for the lazy and unskilled? Here’s one industry veteran’s surprisingly pragmatic take. As your eyes scan the prints adorning the oversized walls of Scarpati’s Belmont Boulevard studio, two truths quickly emerge.

First, the sheer volume of his body of work is difficult to comprehend. The guy has created images—lots of them—for some of the biggest names in music. He served as the go-to photographer for Hollywood’s most outrageous punk and glam trailblazers. Top country artists? Check. Stadium rockers? Yep. Smart young indie pop/rock/alt upstarts? Been there, done that.

The second thing you notice is that there’s something about each shot that effortlessly pushes it at least a few degrees left of center. While Scarpati always finds a new way to get there, every concept cover and portrait manages to feel like a window into its own parallel universe.

Eyes — When you look into someone’s face, the eyes do most of the real communication. So the minute you take that element away, something else has to take its place. In this case, it was the scars.

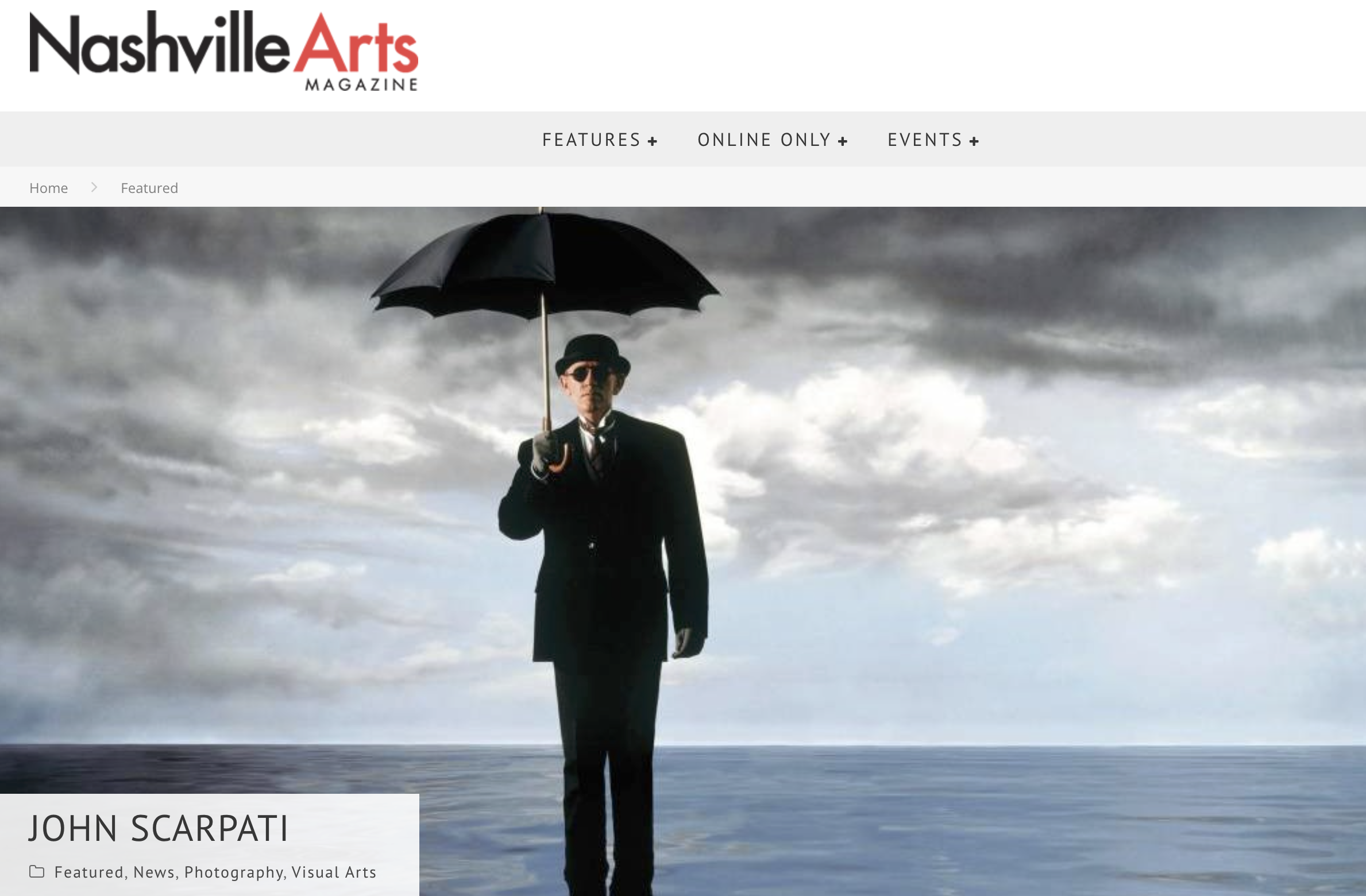

Fear of God — If you know the band Fear of God, you’re probably thinking this shot looks a whole lot like one of their album covers. Except the actual cover features their lead singer. This is a test version.

Clearly, many of these surreal slices of life couldn’t have occurred as actual events. Or at least we hope not.

Take the Rush cover featuring a kid aimlessly kicking a human skull past a wall of giant dice. Or the nude woman who seems strangely placid amidst hundreds of live scorpions, even as some make their way across her bare thighs (done for the German band Scorpions, naturally). Then there’s the plasticine-walled room he did for the New York Dolls, a cover so unabashedly pink that Apple used it in a worldwide ad campaign promoting new iPod colors.

Meanwhile, back here in the real world, Scarpati has finally agreed to sit for a rare interview. The trappings of his workspace speak to the delicate balance between old technology and new: along one wall, restored antique Hollywood movie lights cluster in the shadows like a group of wise elders. Yet high above, in the wide balcony that serves as digital command center, a humming network of custom-built computers feeds a sprawling row of oversized monitors.

Fate’s Warning — This was done for Fate’s Warning. It would have been so easy to take the whole thing very dark and monochrome. But the minute we added the quilt, everything came together

In a city where digital slicing and dicing has become an accepted part of the daily grind in recording studios major and minor, there’s still little agreement on where to draw the line separating art and science.

So what does a top music photographer think?

“If a vocal performance or guitar solo is amazing, and there will never be another that can match it but there’s one bad note, why would you not use technology to allow you to go with the best take?” Scarpati asks.

“It’s no different with photography. In the old days, when a collar was turned up or a stray hair popped out, a stylist would run in, and it’d ruin the momentum. Now, if everybody’s in the zone and you’ve got magic happening, there’s no reason to stop for little things you can fix later.

Snow in June — Shot for a Canadian band called Northern Pikes. They have a wicked sense of humor and were totally on board with the Hollywood casting approach as opposed to putting themselves on the cover.

Toddzilla — First in a series of shots spotlighting some of Nashville’s more interesting off-the-radar personalities. While some call him Toddzilla, to others Todd is known as the Prince of Music City.

“If I get a perfect shot of an artist, but the angle of one of her hands looks a little funny, and there’s a better hand three frames down, I don’t have any problem adding that hand to the hero shot. You just can’t let yourself fall back on technology as a substitute for capturing the moment. The key is making sure you’ve gotten the stuff that can’t be done digitally—the personality, the body language, the expression. That moment where they’re really giving you something.” And what about the rest of the process, after the studio has cleared out and the lights are unplugged?

“I really end up using Photoshop on every image. It’s like mastering an album. You want to record a track well and do a nice mix, but why would you stop short of going into the final tool?

“Look, I’ve been compositing digitally since the 80s. I started using computers for color correction and retouching even before Photoshop. It’s not a new concept. The basics have never changed, even before computers. Maybe we’re not doing it really slowly with stinky chemicals any more, but it’s still the same workflow and process.

For more about John Scarpati visit www.scarpati.com.

New York Dolls — Sometimes the very thing that makes a shot work is the thing that scares people most. The record label called when they first saw this and said they liked everything but the pink. I’m not kidding.